On a beautiful sunny afternoon in early June 2022, I drove up the long winding road to Beckley Park near Oxford. Ahead of me stood a towering, and perhaps slightly wobbly, red brick Tudor mansion with formal gardens that gave way to a stunning and magical wilderness of moats, stepping stones, long grass, and insects flitting through shafts of sunlight. The first sign that this was not a traditional British aristocrat’s home was a couple of seated Asian statues in gestures of prayer. They seemed to be there to welcome visitors and set a serene tone.

Amanda was cheerful and welcoming as she entered the small drawing room by the entrance to the grand house. She was in her 80s, but was sprightly and clearly fiercely intelligent. She was immaculately dressed in various shades of green linen and wore a crisp, white shirt. Although it was summer, there was a fire burning in the room—needed because it was, rather improbably, much colder inside the house than outside. The room was filled with a lifetime’s collection of fascinating objects, on side tables and mantlepieces, that I had barely a moment to glance at before we moved outside.

We sat outside on the lawn, surrounded by clipped box hedges and topiary, and talked. The table was set for lunch in a style that would undoubtedly be described as “boho” by an influencer. There was a purple Indian tablecloth and chunky blue wine glasses. Some of today’s generation use this style to convey the impression of being free-spirited or of leading an unconventional lifestyle. But nothing about Amanda was manufactured. She was an original. She was a 60s-minted counter-culture, free-spirited, and artistic creative. She helped write the book on being a free spirit.

The one thing that most people know about Amanda is that she drilled a hole in her head. While this fact may once have defined her, over the years she moved beyond it to tell a very different story. In later years she said, “Everyone thought I was mad and a little bit bad, whereas now one is just kind of part of the furniture”. No, she was not mad. She was eccentric, like her father—and there is a difference. At 16 she left boarding school and, inspired by her godfather, a Buddist monk named Bertie Moore, and set out alone for Sri Lanka. She made it as far as Syria, where she lived with some desert-dwelling Bedouins before returning home to her draughty mansion.

The hole she drilled marked the beginning of a lifetime of research into human consciousness, first on herself and then by designing and supporting research. She theorised that the hole would enhance consciousness by increasing cerebral blood flow—the hole mimicking the unfused skulls of infants and allowing the brain to expand slightly with each heartbeat. (You can read about how this influenced her in the obituary Ann Wroe and I wrote for this week’s The Economist.)

Her first encounter with psychedelics was in 1965, when she was 22 . She described the experience she described as “the wonderful opening, the mystical experience… and thought this is incredible, but it's almost like a heavenly fun more than a way of life. And so that went on very exciting, euphoric period”. In the 1960s, she and a Dutch medical student, Bart Huges, used LSD as a tool for investigating the mind. When she was younger she had seen her mission as watering the desert; after she met Bart her mission became "watering the desert of the human brain, starting with my own". She wanted to find out how to increase its functionality or vitality.

In the late 90s, the strong taboos around psychedelics led her to found the Beckley Foundation in 1998. Over the following years, the Foundation became a focal point for policy leadership on drug reform and research into psychedelics. Her rigorous approach, and strong arguments for the need for greater access to these drugs, slowly won people over. Today we can trace a line from that work to shifting attitudes towards these drugs from being seen only as dangerous to being recognised as potentially valuable therapeutic agents. Both of her sons are involved in the medical use of psychedelics.

Over the years, she collaborated with many scientists and academics, and co-authored papers. The foundation did the world’s first brain imaging studies of people taking LSD, MDMA, and DMT; and the first human trial of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Her pivotal role is what led me to drive to her home that day.

After lunch, we walked through the gardens. At the edge of the formal gardens, there were some narrow stone doorways. Beyond those was a sort of Tolkien-esque woodland landscape with moats, shafts of sunlight, and mystical little paths—an ideal setting for a psychedelic adventure. At the end of our meeting that day, she invited me back to visit and I imagined wandering around the gardens in a state of enhanced consciousness. However, like the invitation from a young Elon Musk to visit his new firm SpaceX, it is now one of my regretted missed opportunities.

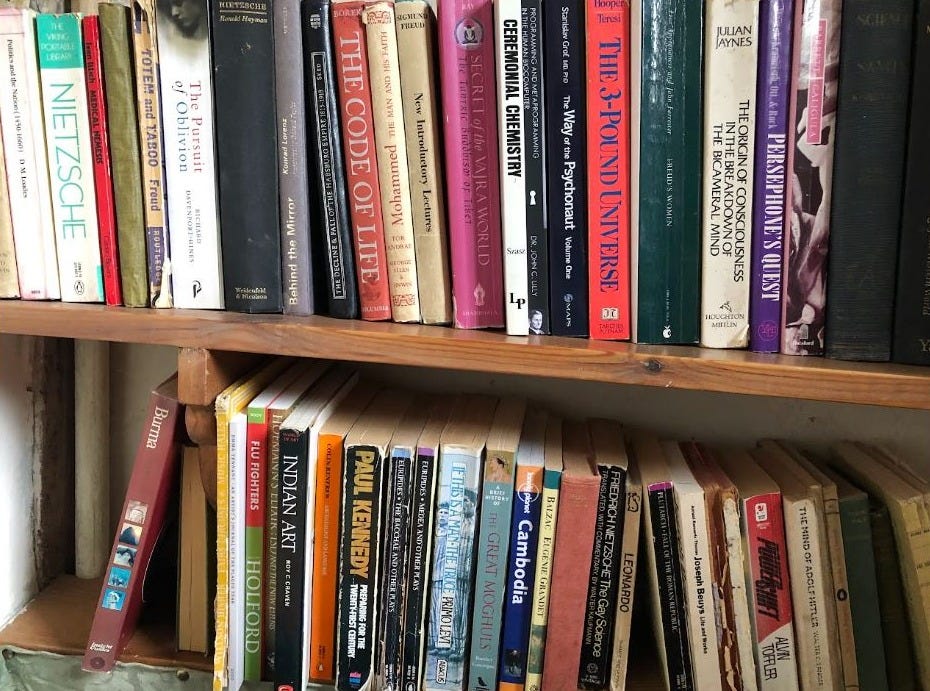

Her mind, like her home, was crammed full of a lifetime of discovery. Books on Indian art nestle alongside books on philosophy, biology, pharmacology, and consciousness.

A few excerpts from the afternoon

So how does one water the human brain?

“I think psychedelics and cannabis and meditation and yoga and exercise and art, and you know all of the things which can do it are tools with which we can fluctuate the level of consciousness, and do, anyhow, without knowing it. People hunt or drive racing cars”.

You said you felt humans had to evolve?

“We're a clever little monkey, but a very neurotic little monkey. You know, we are based on a shortage of blood in the brain, and that's made us have a horrible, tyrannical little ego system, which is very often very badly conditioned to have the wrong values or be traumatised, and be, you know, all sorts of horrible things happen to us. …And so we're a brilliant little animal, but also a dangerous little animal. And then that's we're rather at the kind of hinging point where our technological skills have got clever and cleverer, and our knowledge of ourself our self-knowledge—that's why my doggy is called Delphi, of course, know thyself—And I say the problem of the humans is that their technological skills have gone above their know-their-self skills.

And I think altering consciousness as the ancients all knew is an important veil to kind of remove to see deeper depths. I mean, like all mystics are basically saying that aren’t they? They are saying at the centre, it's all one…. they're expressing very highly intelligently, their experience of high-level [autostates?] in the state of bliss or whatever. But I think what we can now do is more exactly to start to work out what it is underlying and therefore that gives us added control of how we use our brains which is useful.”

On death, and the fear of it, and psychedelics

During the afternoon Amanda was excited about the potential for microdosing in neurodegenerative illnesses like Alzheimer’s and was inspired by an account of a 97-year-old woman who had microdosed with LSD, and was seemingly “brought back to full consciousness of self”. (Interesting sidebar: Johns Hopkins is currently doing a small, open-label study in 20 patients with Alzheimer’s which is due to end later this year.)

She was very excited about the potential of these drugs to address existential fears surrounding death and mentioned work by Johns Hopkins on psychedelics at the end of life. (This study looked at 51 cancer patients who experienced significant anxiety or depressive symptoms and found that a dose of psilocybin—given with supportive psychotherapy—led to notable increases in ratings of death acceptance and reductions in anxiety about death.) She said many felt that it had changed their experience, and there was a wonderful quote from a woman who said it was like “being hugged by God”. “It didn’t stop them from dying, but it changed their experience, their perception, and their reaction to it, so it can be a wonderful help. We should use all these technologies to improve life.”

There is a short and beautiful account of her final days on the website of her foundation. She died on May 22nd, 2025. During her final two weeks she lived with “courage, curiosity, compassion and gracefulness”, surrounded by her family and closest friends.

“She did not ever lose her love of life, but she did turn her attention to her next great adventure. She made clear that, far from being afraid, after a lifetime spent equally fascinated by the scientific as by the mystical, she was excited to be on the cusp of discovering the ultimate mystery.”

If you have read this article, please like it and share it.

You may also enjoy:

Doing drugs at Davos

Every year in the tiny Swiss mountain town of Davos, presidents, prime ministers, billionaires and a hefty chunk of the global elite gather to hobnob and push their agendas. The main event in town is the World Economic Forum. It is coming again soon. Don’t hurry over. For lesser mortals like you and I, it is an e…