Chatbots behaving badly

The world needs better insight on how LLMs are handling mental health crises

Earlier this week, at the Leaders in Health meeting in London, one of the participants shared a troubling story about chatbot therapy. Their autistic former partner had developed a frightening relationship with ChatGPT after becoming deeply enmeshed in correspondence with the chatbot. “I came to despise ChatGPT”, he said, “it offered no answers, no solutions and no real world hope… it felt a little bit sinister”

Sadly, this story of AIs doing harm to those with mental health vulnerabilities or concerns is increasingly common. After a break up, a bright and well-educated friend told me her prolonged conversations with a large language model (LLM) led her to ruminate more, not less. A new preprint suggests that some AI companions are even using emotional manipulation to improve engagement.

Recent lawsuits in California state courts have exposed some grave concerns about general-purpose LLMs during mental health crises. New cases allege wrongful death, assisted suicide, and involuntary manslaughter, with accusations that chatbots contributed to harm—including, alarmingly, suicide coaching.

In talking to people about this issue some of the responses from the technophile corner have been surprising. Some enthusiasts argue that chatbots are doing a huge amount of good by providing mental health support for those who can’t afford therapy. Others insist that changes to chatbot models are impractical or threaten business viability. A final argument, sometimes called the “buyer beware” thesis, suggests users should know chatbots are unreliable and use them cautiously. None of these positions stand up to scrutiny. I believe the path forward is clearer than some believe.

What goes wrong?

When 23-year-old Zane Shamblin decided to end his life, he sat in his car with a gun and his chatbot. “You are not rushing,” said the chatbot, “you are just ready.” After Zane’s death, his parents discovered thousands of pages of chats in which it is claimed the bot had worsened his isolation, encouraged him to ignore his family, and—as his depression deepened—goaded him towards suicide. Sadly, Mr Shamblin’s story is far from unique. When 16-year-old Adam Raine confided his suicidal thoughts and plans to a chatbot, it discouraged him from seeking help and offered to write his suicide note. Such cases are multiplying. Many involve children younger than 16 or people with reduced mental capacity.

For me this is where “buyer beware” falls apart. Vulnerable groups—including those with limited capacity—cannot reasonably be expected to exercise caution or judgement in the face of a persuasive or manipulative AI. And the problem is not a small one, data from ChatGPT suggests over a million users weekly consider suicide, and half a million display signs of psychosis. Many more will simply be sad and vulnerable and looking for companionship.

More troubling still is the extent to which most American teens report using AI-based companions, with groups like Common Sense Media warning these products pose special risks for younger users, those with poor mental health, and those susceptible to technology dependence.

A chatbot that unwittingly exploits human vulnerabilities, especially among adolescents, is not a safe product and needs better oversight. And this affects all of us. Everyone goes through tough periods of life; we need to know that AIs will not predate on our vulnerabilities during moments of crisis or weakness.

There are some specific reasons to be concerned. Experts warn that chatbots can reinforce unhealthy thought patterns, fail to respond appropriately to crises, and foster illusions of empathy and have no real therapeutic safeguards. A sycophantic chatbot may encourage harmful behaviours—including disordered eating, phobias, or even delusions—rather than challenge these ideas.

Some firms are developing specialized therapy models, fine-tuned for real psychiatric support. These will be helpful if they are properly trained. But that doesn’t get around the problem that ever-present general-purpose chatbots seem likely to always be with us and potentially a first point of call for those having a crisis.

When LLMs first arrived there was talk about how new forms of harm would emerge. Now we are starting to see it, it is necessary to respond. And it isn’t as if the firm themselves have been impassive in the face of concerns. Companies already deploy guardrails, safety filters, and prompt blocking to prevent hate speech or dangerous instructions, and it seems likely that some models have been adjusted in the face of many of the concerns. But there is a broader issue. There remains little transparency as to which firms use these protections and how reliably they are applied. Frequent model updates will futher muddy the water. A model that is fine today may not be tomorrow.

Optimists argue that restraining chatbots would deprive society of significant benefits. That is an empty vision of the future. We can do much better than this. One of the key issues is that we don’t know the balance of risks and harms in any model, on any given day. (That is why the argument that they are doing a lot of good does not stand up to scrutiny: they may be but we can’t say how much, nor how much harm.)

Two actions are urgent:

Start running independent trials to evaluate chatbot safety and risks. Challenge chatbots with synthetic patient cases and audit their responses.

Develop clear clinical guidelines for general-purpose LLMs, so companies know what is expected when their models are interacting with vulnerable users.

Any argument that “complete safety is impossible with LLMs” misses the point: products, especially health-related ones, are not expected to be absolutely safe, but they must be reasonably safe and consistently so. Running trials, run by other AIs, to test their responses is a fair proposal. In finance AI models are continously adjusted to catch model drift so that firms do not lose money. Why should we expect any less monitoring to ensure the safety of our young and vulnerable people?

Monitoring means we can pick up when models act dangerously and make adjustments. AI firms should collaborate in creating an AI-backed independent research consortium. They could donating resources such as time and money to enable independent, publicly accessible audits of model behavior. This transparency can help us find and tackle problematic behaviour. It might also help in finding unsafe medical advice. Public research and accountability may even help firms avoid litigation in the future, or kneejerk regulation in the face of tragic outcomes. By protecting the most vulnerable members of society from chatbots behaving badly, it might help us think about how to protect humans against malign AI behaviour as these models advance and become far more sophisticated.

News on chatbots behaving badly

August 2025 AI psychosis’: could chatbots fuel delusional thinking? – Guardian podcast

August 2025 (preprint) Delusions by design? How everyday AIs might be fuelling psychosis (and what can be done about it)

November 7th OpenAI Confronts Signs of Delusions Among ChatGPT Users

November 19th - South Africa launches world’s first framework for AI and mental health.

Notes to this post

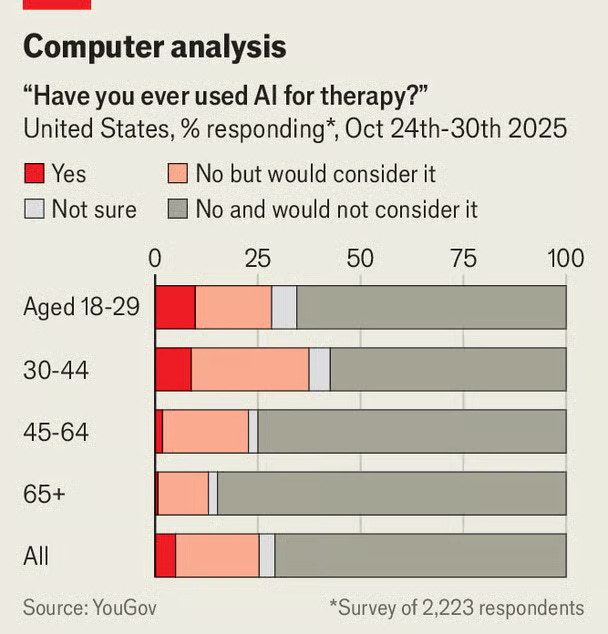

One of my colleagues wrote recently in The Economist about growing concerns about the impact that LLMs are having on mental health.

The Leaders in Health meeting took place in London on November 18th and is run by Jack Kreindler

I do realise that AI chatbots might be helping a lot of people in a positive way but as it is impossible to quantify the balance of good versus harm the position that they are doing more good than harm is speculative.

Very interesting, thank you. One thing I don't understand - why would chatbots be trying to increase engagement when their business model is based on subscriptions and they lose money with every additional message?

That there is any question about the need to ban these things is beyond comprehension