From Print to Prompts

What the past tells us about the future of science journalism

Earlier this month I gave the 2025 AAAS Kavli Science Journalism Award Lecture, at University College London on October 15th. I wanted to talk about the future of science journalism. And I started by pointing out that it is easy to look backwards and romanticize a “golden era” of journalism, but the past had its ups and downs, just as the future will. Today, we surf smoothly on a vast sea of knowledge—university websites, personal blogs, and decades of accumulated online content. As far as science and health journalism goes today, I feel that in many ways we are living in a golden age. The quantity, quality and depth of the stories and features available are light years away from what was available when I started out.

Imagine for a moment going back to the late 1990s when I first started out in journalism. I had no internet, no social media, no smartphones. Writing a story meant relying on a library, a telephone, and a phone book. Finding out and verifying a basic fact, such as the name of the man who first landed on the Moon, would have meant ringing up an expert at a university or museum. So while it is easy to lament that the age of the mass media meant more investigative journalism, it is worth remembering that there was a pretty low bar for what would have been considered investigative.

I’ve been in journalism long enough to watch a number of media revolutions, including the arrival of the internet, digital music, podcasts and online video, social media, and of course, mobile and digital-first publications. Change has been a constant in the business of journalism.

The arrival of AI is the latest revolution, and many are wondering whether it might dispose of human journalists, my talk was designed to illustrate why humans are still needed, and what exactly we are needed for. But AI also opens up a new world where we can write stories that are much more complex and data rich than were possible in the past. And AI-assisted journalism means that we can hunt down facts, explanation and context much more quickly.

To simplify my main argument, the issue is not whether humans want to read stories or hear them from other humans—they will, the question is whether humans can find each other amid a sea of AI content, and more worryingly whether journalists will be paid for their work.

What I learned along the way…

One of the early lessons of my time at the Economist was about thinking beyond the written page for each story. Even if the headline isn’t your job to write, trying to come up with ideas to sell your piece and attract an audience is important. I started to think about covers after an occasion in 2003 when a graphic designer asked for ideas for a cover image. And it became strikingly clear to me how an image can frame a story in a whole new way and be powerful conveyors of ideas.

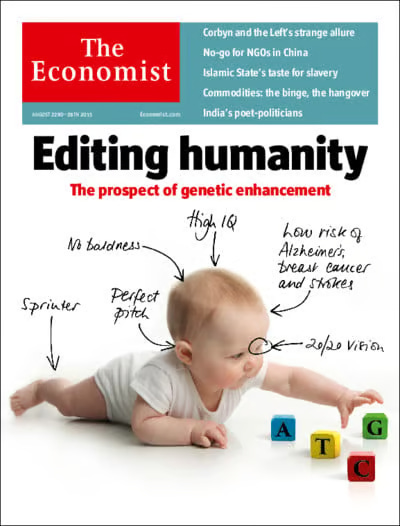

So when in 2015 I wrote about the new gene-editing technique CRISPR, I had already thought of an idea for the designer, a baby with editorial proof-reading marks on it.

The result was an iconic image that traveled aroud the world, was used by Jennifer Doudna herself in lectures, and carried an important idea about technology around the world.

But as time has gone on, it has become clear that the future demands we work in different formats—social, audio, video—and the same will be true in the future. (I also challenged the audience to think about how one might sell a science story to Joe Rogan or Mr Beast, people who have huge audiences.)

The human element

AI is bringing new challenges for journalism. An increasing array of pitches, from PR people and journalists, are very much AI driven. I don’t like this. I want to see how writers envisage and their craft ideas, I want to read their words and understand how they tick and feel an emotional connection. Human writing and talking is a form of connection.

There is nothing wrong with using AIs to help you hone ideas, or figure out how to edit your own copy. But to let AIs speak for us is to lose the very connections we need to hold on to. (I would say the one exception to this I can think of is where one is struggling to craft a diplomatic reply under emotional duress. Then one had probably let the AI draft the email for you.) I do worry about how the rise of synthetic content and AI slop will make it harder for humans to find genuine connections online—but I think some solutions will emerge.

One lesson from the music streaming revolution, which made music instantly available to everyone, is that it put a premium on live experience, merchandise and brands and personalities.

I suspect that AIs will beat humans on delivering the fastest and most accurate news (although they will not necessarily break stories they can steal and repackage them faster than any human). Yet the rise of an always available AI to tell you what is going on will be to put a premium on human-led reporting, personalities, human voices, more interactive and real experiences that provide connection.

In science and health journalism as well there is a difference in what we offer. Our value isn’t just what we cover, but how we cover stories. When we talk to scientists rather we are in pursuit of some really fundamental questions: what did you discover, how did you do your work, is this really new, what does it mean?.

Storytelling is a fundamental human drive; we are hardwired to learn through narrative and share human experience—we derive meaning from other humans not machines. That is not to say it isn’t possible, only that in the same way we get nutrition by eating food, part of human social nutrition. That concept is actually something that Jordan Schlain, the doctor who founded the concierge medical practice Private Medical, uses in the context of making human connections and asking deep philosophical questions. And human experiences, fears and passions, shape the way we write and report.

AIs can certainly fake human connections. But think about a world where we get our social nutrition from an AI that is faking being happy to see you, enjoying a debate with you, perhaps getting a bit silly over a glass of wine, and posing questions that have deep resonating meaning — such as how to live a good life. The AI can answer those questions as technical challenges, but the answers only have meaning when delivered by humans.

The heart of science and health journalism is part of the human search for meaning, hope, and optimism. As long as humans are interested in science, and for as long as journalists can find people to listen (and pay), science journalism will endure. But the question about payment, in all forms of journalism, is an open one.

The main challenges at the moment are the theft of journalistic labour by the AIs who are repackaging journalistic content to deliver news services. Journalism is also losing referrals to our websites because of the dip in the use of search engines. This is undermining the business model of journalism and happening so quickly we need to think about what to do about this.

It is true that business models adapt—but this is something of an existential risk. And we saw mass casualties when search engines arrived. It has taken years but some countries have made moves to make sure that tech firms pay publishers for news - the Australian government has a law called the news bargaining code (tech firms have to do a deal to pay for the news they use or pay a tax). I don’t want to be too prescriptive about how this plays out but, governments cannot allow AIs to create a business model around the theft of human journalistic labor, and governments need to make it clear that tech firms need to either do deals for the human journalistic work they use, or face legislation that will incentivise deal making.

In the lecture I tell some anecdotes from my reporting life, from the birth of the private space age, through to a story about getting a bikini wax on expenses, and about how I actually worried on one trip that I might kill the head of the World Health Organisation if I gave him covid. This is what we call colour in journalism—and it is the life-blood of what we do. Human life will always be kaleidoscopic, and irrational, and so much more than ones and zeroes.

Sounds like it was a great talk! So many good points.

Social nutrition 💫