On February 23rd 2023, the government of Cambodia reported than an 11-year-old girl had died from an H5N1 avian flu infection. The news came amidst heightened concerns over the global spread of avian influenza, which is tearing through wild bird and poultry populations. Avian influenza is also being picked up by a variety of mammals such as sea lions in Peru, otters and a mink farm in Spain. All of this is causing concern over the potential the virus has to trigger a pandemic.

Avian influenza has been a rising concern since an outbreak in 1997. As this 2005 cover from our archive shows, there have also been previous times the world has worried a pandemic was imminent. For this to happen, the virus would have to acquire the ability for efficient human-to-human transmission—something that it has not yet managed to do. H5N1 is not yet well adapted to infect our upper respiratory tract.

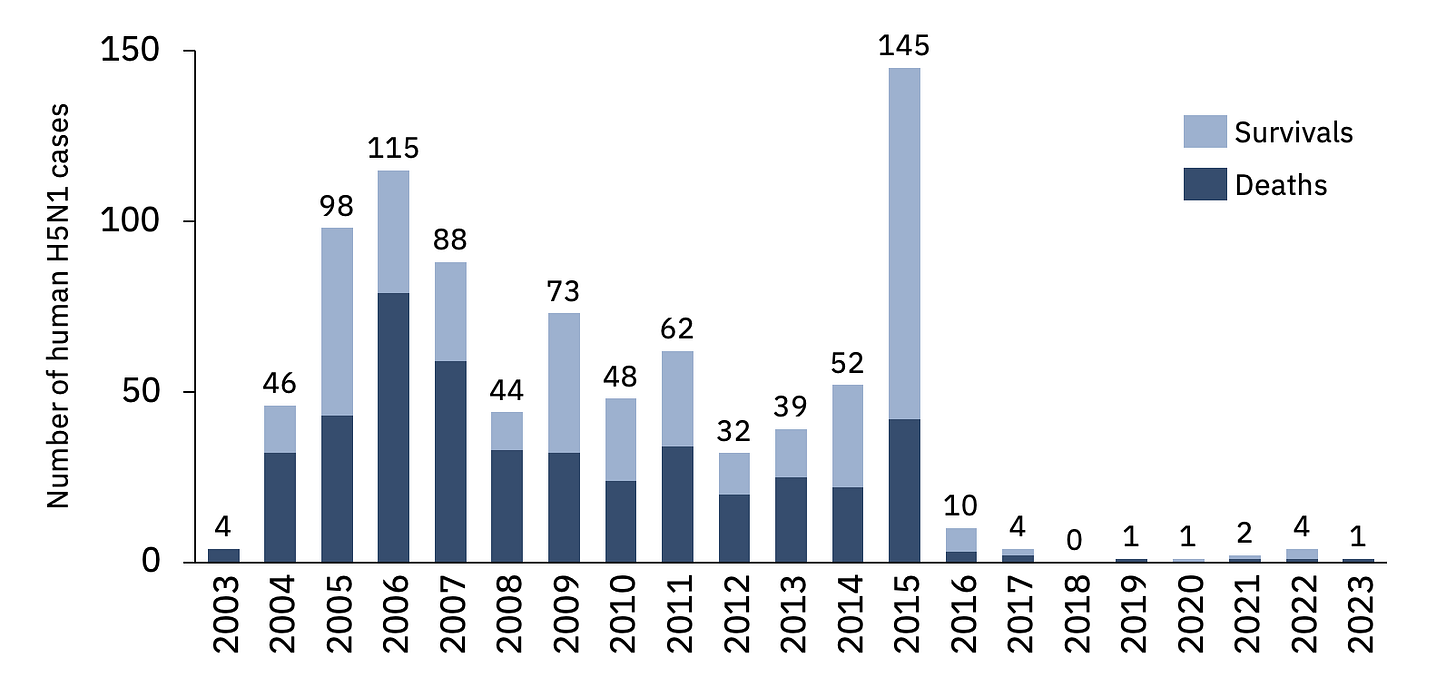

For now, human cases of H5N1 are thankfully rare and are mostly connected to contact with poultry. But when they happen they can be deadly and they do threaten the young as well as the old. (Note that this chart showing high rates of fatality may be biased by undersampling of asymptomatic or low-grade infections.)

Before covid-19 many thought the next human pandemic would be caused by an influenza virus. The 1918 pandemic was an influenza virus with genes of avian origin. It killed about 50m. Flu pandemics also occurred in 1957-58, 1968 and 2009. How likely it is that current strains of avian influenza could trigger another pandemic is entirely unknown. It is not possible to predict what will happen.

In 2005, as a junior science journalist I urged us to run a cover that alerted the world to the risk of an influenza pandemic. Earlier in the year, Laurie Garrett had written a terrifying account of what one might look like in Foreign Policy. I was worried. But I found it hard to convey the urgency of the need to prepare to my more sceptical political and economic colleagues. The leader, “On wing and a scare” was much less forceful than I wanted. It even set the case for preparing alongside the case against! Although we came out in support of preparing more, the impetus was watered down by phrases like, “In the case of this avian influenza, there is even less known of the scale or likelihood of the threat than with terrorism. The threat of a pandemic may fizzle out entirely”.

Covid has focused minds. A few weeks ago, I was urged by economists on our staff on the question of what the world should be doing to prepare for an avian flu pandemic. In a classic “No shit, Sherlock” moment they pointed out that the costs of covid were absolutely enormous. This, they said, is a tail risk. (A small probability event that will have huge financial consequences.) Surely it is worth doing more to prevent another one, they wondered, or plan to respond better if another occurs? (Tireless advocates of better pandemic public health policy are allowed an eye roll and a sigh of exasperation at this point.)

The economists get it, so maybe it is time for the politicians to get on board? Certainly the world does not know how big or how dangerous the next pandemic is going to be. Or when. But there is going to be one. And it is becoming more likely, not less, as our world becomes ever more connected, and messes around with natural habitats and wildlife farming. And also tinkers with pathogens in laboratories. Risk is rising and the costs are enormous.

Last year the International Monetary Fund estimated the cost of the covid pandemic could go beyond 12.5 trillion by 2024. An influenza pandemic could well be worse, particularly as it could well strike at the young, as well as the old. This would deepen the human and economic impacts.

The potential costs of preparing are tiny in comparison to the scale of these pandemics. We now know that we need to think beyond individual diseases. Rather ironically we had done quite a bit of preparatory work on influenza, but then covid came along. This preparation involved setting up a global network of sites that manufacture flu vaccines. There was also an agreement that the biggest manufacturers of flu vaccines would give 10% of their doses in real-time for global distribution. Years ago flu vaccine manufacturers also started to contribute to a fund to distribute vaccines in return for seasonal information about the strains in circulation. About ¼ billion is ready to deploy.

Work is under way advancing candidate vaccines for all sorts of pathogens that might emerge. Moderna said last year it would begin testing vaccines for 15 of the world’s most worrisome pathogens by 2025. The non-governmental group the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation has invested in 21 vaccine candidates. Progress on a universal flu vaccine has been slow. Recently, Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, a biomedical charity, wondered whether another good option would be to develop vaccines against all the different types of flu. Influenza viruses are divided into subtypes based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). This gives 18 different hemagglutinin subtypes and 11 different neuraminidase subtypes.

Few of us probably want to think about the next pandemic. We have to. Member states of the World Health Organisation are currently negotiating a pandemic treaty and revisions to International Health Regulations. Success will come if countries are able to create a wide-ranging and strong deal that creates incentives to co-operate between countries and companies Current geopolitical difficulties need to be overcome. Viruses know no borders. And despite the cynicism about pharma companies, ultimately they will do what governments tell them to do. So the political agreements have to come first.

We already know what might be useful. The arrangements made for donation of real-time production of influenza vaccines need to be extended to all pandemic vaccines, diagnostics, and medicines such as antivirals. Extending this to 20% of real-time production would be a good idea. A binding treaty would make it harder (although not impossible) for countries to halt the export of vaccines during a pandemic. It isn’t just rich countries that get selfish during a pandemic. Middle-income India was reluctant to export vaccines when covid was running rampant.

Vaccine nationalism is impossible to eliminate, but with an international deal, and regional production hubs, the dynamics of vaccine supply during a pandemic would improve. Another shift that is underway is that the technology to make a range of different vaccine types (including mRNA), is also spreading globally.

Intellectual property is also part of the discussion. It will be difficult to settle. That is part of a longer discussion. Morally, it is obvious that IP rules shouldn’t be an impediment to saving lives during a pandemic. But equally, they incentivize the creation of novel products which would not otherwise exist. Would Pfizer and Moderna have bothered creating vaccines for covid if they knew they would have to hand over IP? That is why the use of favourable licensing, as was done through the Medicines Patent Pool, has been so helpful.

There are other challenges. Although the world needs better surveillance and prompt notifications of notable or suspected pathogens by countries, such prompt notifications can lead to negative consequences. Many countries initiated border closures when South Africa announced the emergence of the omicron variant. Moreover, the countries that share pathogen data are not impressed that they may be last in line for the products that emerge from this sharing of knowledge.

The world needs to find new ways to cooperate on health—even in this age of rising geopolitical mistrust. It was against the backdrop of the end of the second-world war that the world decided it needed a new department of public health. Andrija Stampar, a round-faced, bespectacled, Yugoslavian doctor, opened the first-ever World Health Assembly (WHA) in Geneva in 1948 that birthed the WHO. The need for co-operation has only grown. But so too have the complexities of the science and the politics.

There is no way to get to a safer world without better global surveillance, tighter control of the wildlife trade, wildlife farming, and better laboratory safety and oversight. All countries need to do their bit. The next pandemic is just a matter of time—although it can be delayed, some outbreaks can be halted. It could be a decade away, it could be tomorrow. The news might start with an announcer saying not that a single child has died, but that dozens of people have been hospitalised due to an unknown outbreak. The world needs to have a plan. As for avian influenza it needs watching closely, with outbreaks in poultry being dealt with. The more global agreement and cooperation and finance that can be agreed upon ahead of time, the lower the risks to lives and livelihoods.

For more detail on global preparedness negotiations se

Health Policy Watch: Five Priorities to Global Pandemic Preparedness

Nature: What the WHO’s new treaty could mean for the next pandemic

Reuters: Draft WHO pandemic deal pushes for equity to avoid COVID 'failure' repeat

STAT: The WHO’s new pandemic treaty is good for the world — and the U.S.

(sigh of exasperation) Great post! Among other sensible investments in preparedness would be better hygiene interventions. Not only does simple handwashing mitigate tail-risks, it pays dividends along the way in the form of reduced child mortality and stunting (each and every year). Win win! However, the vast majority of hygiene interventions today are mass awareness-raising campaigns that generate poor results. Several high-quality evaluations have concluded that awareness doesn't move the needle, and that actual handwashing is done most frequently when a desirable sink is conveniently located. For that reason, robust portable handwashing stations that don't require plumbed/grid water represent one of the least sexy—but perhaps most compelling—ways to dramatically improve global public health and mitigate pandemic risk. Not by 2030, but sooner.

Perhaps the biggest risk to humans in future pandemics is the permanent distrust people now have in the political, pharmaceutical and medical establishments due to the mishandling of failed policies (lock-downs and mandates) and efficacy and safety of the quasi-vaccines.