Does drinking tea reduce senior moments?

Scientists wonder if flavanols are nutrients for ageing brains. New research on these plant compounds adds to growing evidence of the strong links between nutrition and brain health

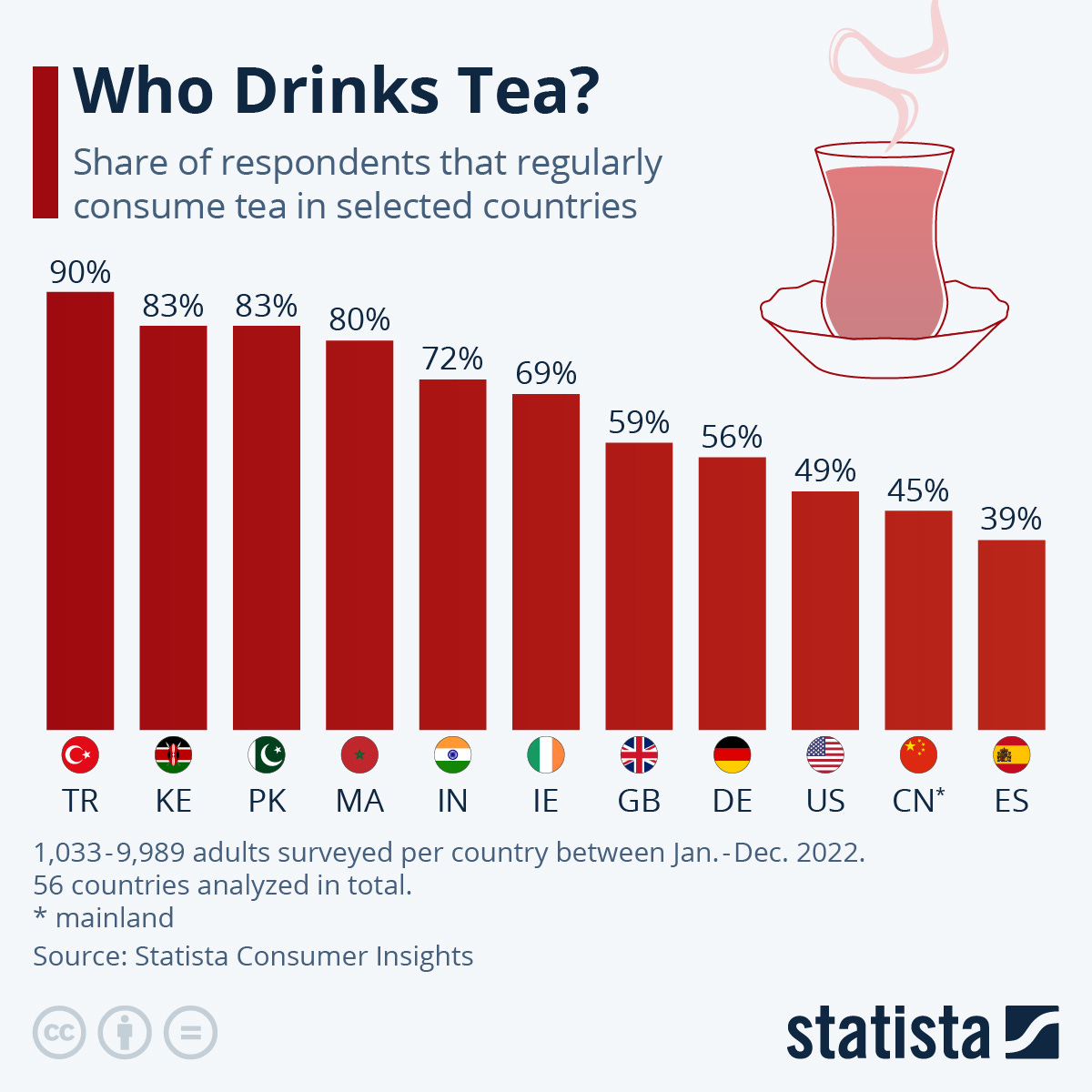

On December 16th, 1773 American colonists threw hundreds of crates of British tea into the Boston Harbour. Besides helping kick off the war of independence, it also triggered a trend for drinking coffee. And while Americans can console themselves with the birth of the largest and most dynamic economies in the world, they may have made one error that day. It seems that, thanks to a set of chemicals called flavanols, the consumption of tea—as well as berries and cocoa plants—may help reduce age-related cognitive decline, the losses in thinking speed and attention that come with age.

That, at least, was the conclusion of a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on May 29th. Nutritional studies have a reputation for being flaky. But this paper reported a result from a large, three-year randomised-control trial (RCT) known as COSMOS, which tracks more than 3,000 people. RCTs, which randomly assign their participants to receive either a treatment or a placebo, are the gold standard of medical evidence.

At the start of the study those who consumed fewer flavanols in their food scored less well in tests of memory. During the trial, men and women over 60 were randomly given 500mg of flavanol extract or a placebo. The participants completed a number of memory tests—one of which involved learning a list of 20 words, and remembering them again after a 20 minute delay.

When looking across the entire trial population the supplement did not improve memory. But the researchers had also hypothesised at the outset that supplementation would have a more pronounced effect on those already eating low-flavanol diets. Sure enough, those with poorer diets did indeed see a small—but significant—improvement in memory. And, crucially, the researchers were able to use urine tests to show a relationship between performance on the memory tests and increased levels of flavanols in the body. Although questions have been raised about how meaningful the response is, the results fit with previous studies on animals and humans1 suggesting that flavanols improve cognitive function. For example, one prospective study last year concluded that eating flavanols could slow the rate of cognitive decline in humans.

Exactly what these plant compounds are doing remains unclear. Clues, say researchers from the most recent study, point to an area of the brain called the dentate gyrus. This is connected to the hippocampus, which sits near the bottom of the brain’s two hemispheres and is involved in memory and recall. The authors of the new paper say this area of the brain is enriched in growth factors that other studies show seem to engage with a particular flavanol called epicatechin. The implication is that epicatechins might be stimulating the growth of neurons in this area of the brain—although that wil need further studies to establish. The strength of the findings, though, led the authors to propose in a recent press conference that flavanols may even be a nutrient for ageing brains.

There are other health reasons for those with poor-quality diets to consume more flavanols. Last year, The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics proposed a dietary guideline for flavanol intake of 400 to 600mg a day on the basis of its benefits for cardiometabolic health. The message from this new research is an old one: get a good diet with a range of fruits and vegetables. Although the supplements used in the trial were from cocoa, a special extraction process was used to obtain the flavanols. Eating chocolate, then, will not necessarily deliver the same benefits.

Drinking tea, too, though will help as it is an excellent source of flavanols. Between one and four cups a day, depending on the black tea itself, should be plenty.

There is, though, a ceiling effect. If one already consumes a plentiful supply of flavanols, taking more will not help you. At this stage there is no evidence of any impact on brain-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. But given the links between cardiometabolic health and dementia it wouldn’t be surprising if one eventually emerges. Boston, perhaps, needs a new kind of tea party.

Food for thought

The links between nutrition and the brain are worth highlighting again. Earlier this year The Economist published an essay by me on this topic. The piece examines the relationship between food and the mind, and focuses on how food affects our wellbeing and cognition. It looks at several studies indicating the significance of nutrition in cognitive development and mental health, and emphasises the importance of a balanced diet for wellbeing and intellectual performance. It also shows that processed foods are harming us in ways that traditional cuisines used to avoid.

One recent study concludes that sticking to the “Mediterranean diet”, high in vegetables, fruit, pulses and wholegrains, low in red and processed meats and saturated fats, decreases the chances of experiencing strokes, cognitive impairment and depression. Other recent work looking at a “green” Mediterranean diet high in polyphenols (the antioxidants found in things like green tea) found it reduced age-related brain atrophy. Another version, the mind diet, emphasises, among other things, eating berries over other kinds of fruit and seems to lessen the risk of dementia.

Studies in animals show that when they are fed a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids (from walnuts, for example), flavonoids (consumed mainly via tea and wine), antioxidants (found in berries) and resveratrol (found in red grapes), neuron growth is stimulated and inflammatory processes are reduced.

For more on this topic, read the essay.

Kempster SA, Khan KM, Williams CM, et al. Flavonoids from cocoa improve cognitive function and increase cerebral blood flow in aged rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(14)

Smith AD, et al. Blueberry supplementation improves cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Nutritional Neuroscience.

Shang X, Chen G, Wang Y, et al. Flavonoids from cocoa improve cognitive function in healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2015

Now I know why my English wife is so lucid even though she is a senior citizen like me.