The post-truth pandemic

Political leaders and states have distorted, abused, and misused science throughout the pandemic.

Imagine, for a moment, that a massive asteroid is hurtling towards our planet. You would think that science, technology, and facts would form the backbone of the response. World leaders would be expected to come up with a strategy, informed by the world’s most brilliant minds, for how to deflect the asteroid. Or failing that, preserve as many lives as possible.

The last couple of years have taught us something. Should this hypothetical asteroid threaten us a number of far more depressing scenarios seem likely. Some leaders will deny the asteroid exists, or lean on non-mainstream ideas that suggest the rock is actually going to whizz right past us. Other politicians would point out that a large asteroid impact is not so bad, really. You know, not much worse than a bad meteor shower. And some would use the crisis to their advantage, spreading division along the way. Belief in the asteroid could even become a sort of political litmus test.

Strange days indeed

Over the last few years, one of the questions I’ve been asked the most often is what it was like to be a health journalist covering a pandemic. One thing that stood out was the volume of misinformation that spread from the early days, and the extent to which the infodemic was driven by political leaders and states. So much so, I started to think about the outbreak as a “post-truth pandemic” about halfway through 2020.

Stranger still was the degree to which the infodemic was driven by the leader of the free world. Researchers at Cornell University analysed 38m English language articles, published between January and May 2020, about the pandemic. They found that Mr Trump featured in 38% of the “misinformation conversation”, and concluded he was likely to be the largest driver. Mr Trump’s vast platform, amplified by the media, helped drive a firehose of misinformation and distrust with consequences that rippled around the world.

Mr Trump’s disinterest in science was apparent throughout the pandemic. For example, in his downplaying of the seriousness of the pandemic, or in his promotion of an unproven malaria drug, hydroxychloroquine, as a treatment for covid-19. (The media helped with this, too. During a two-week period between March 23rd and April 6th 2020, Fox News mentioned the drug nearly three hundred times. )

Behind the scenes, Mr Trump pushed hard for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—run by Stephen Hahn—to approve convalescent plasma and hydroxychloroquine. A new book by Brendan Borrell, The First Shots, describes how the president called his health secretary barking: “Did you see my tweet? Why hasn’t the FDA approved convalescent plasma? Is it that fucking Hahn again?” That approval came. As did one for hydroxychloroquine. Experts tried to push back, arguing that there was a lack of evidence to support the use of these treatments. This was interpreted as “anti-Trump intent”, says Kathleen Hall Jamieson in an article in Nature Human Behaviour.

The deep state, or whoever, over at the FDA is making it very difficult for drug companies to get people in order to test the vaccines and therapeutics. Obviously, they are hoping to delay the answer until after November 3rd. Donald Trump, Twitter, 22 August 2020.

Hydroxychloroquine was given an emergency use authorisation on March 28th,2020 by the FDA. According to the book, “Uncontrolled Spread”, by Scott Gottlieb, a former FDA boss, by May 19th the FDA knew the drug was linked to 400 adverse health events and 87 deaths. Yet the White House still wanted the drug distributed widely. On July 1st that the FDA withdrew its authorisation. Only then did it post its May 19th report.

While China was receiving plenty of well-deserved criticism for refusing to share data, and silencing its scientists, it was hugely ironic that America’s Centres for Disease Control (CDC) was also muzzled. This came after its press briefings failed to echo the president’s upbeat accounts of the outbreak. By May 2020 cardiologist Eric Topol warned in a tweet of, “a relentless, destructive crusade” against science and medicine. Around the same time, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), an American NGO, warned that health information was being mischaracterised on a near-daily basis by political officials. UCS said the silencing of the CDC was entirely at odds with how the American government had approached public health in the past. By contrast, in 2003, during the first weeks of SARS, CDC press events outnumbered presidential press events.

Mr Trump’s alternative facts were influential. Particularly with Brazil’s populist president, Jair Bolsonaro. He was an eager recipient of Mr Trump’s medical wisdom. The two met in March 2020 for dinner in Mar-a-Lago, Florida. Here Mr Bolsonaro acquired his interest in hydroxychloroquine. The next month Mr Bolsonaro fired a decent health minister who opposed using the drug. The fired minister told the New York Times that after Mr Bolsonaro met Mr Trump, “it was very hard to get him to take the science seriously”.

The Times also revealed that Mr Trump and Mr Bolsonaro worked to undermine the Pan-American Health Organisation (PAHO) because it had worked with Cubans. During a pandemic, the American administration nearly bankrupted the agency. And of course, we know that the American administration also attacked the World Health Organisation (WHO) during the pandemic undermining its standing.

The rift between Bolsonaro and the facts was so vast the editors of The Lancet, a medical journal, felt it necessary to warn, in May 2020 that the biggest threat to Brazil’s covid response was the president himself. It accused him of sowing confusion and discouraging sensible measures such as physical distancing and lockdowns. Mr Bolsonaro also dismissed the virus as a media fantasy and a trick, and he tried (and failed) to suppress publication of the daily death toll. Of the arrival of vaccines in the country he said he would refuse one remarking, “if you turn into a crocodile, it’s your problem”. Later his “anti science” government was blamed for much of the devastation in Brazil.

Other notable alternative facts from global leaders:

Drink hot drinks because heat kills the virus. Argentinian president Alberto Fernández, and health minister.

Covid-19 has been eliminated by God. President John Magufuli declares Tanzania free of covid-19 in June 2020

Herbal tonic is a “miracle cure” for covid. President Andry Rajoelina of Madagascar.

Drinking warm water can flush away SARS-COV-2. Malaysian health minister

“It is not terrible or fatal. It is not even as bad as the flu.” President López Obrador, Mexico

There are no confirmed cases of covid in Turkmenistan or North Korea, something the World Health Organisation says is unlikely.

Covid-19 is an American biological weapon created against China. President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela.

AstraZeneca vaccine seems “quasi-ineffective” in older people. French President Emmanual Macron.

The infodemic story gets more complicated with China and Russia. A recent article by Sascha-Dominik Dov Bachmann, a professor of law at the University of Canberra, and colleagues, says the pandemic has ushered in a golden age of information warfare with Russia and China using digital media and other capabilities to consolidate their authoritarian rule as well as undermine and disrupt the liberal international order.

The scope and extent of the information “management” by China is beyond the scope of this piece1. The government detained and vanished many who tried to speak about what was happening, blocked the flow of information from scientists, delayed sharing vital health and scientific information, and engaged in a variety of efforts to suggest that the virus originated from outside of China—including an imaginative tale that it came from lobsters in Maine.

As we watch another explosive wave of covid unfold across Europe, remember that both Russia and China worked in this region to undermine trust in Western vaccines and EU institutions. The Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) says Russia spread the idea that vaccines contained nanochips into the blood to track people. Earlier this year, CEPA warned that disinformation worked in Central and Eastern Europe, and that one-third of the region’s population believed that covid-19 was fake, and one in four believe the virus was deliberately made in America. There was a correlation between acceptance of covid-related conspiracy theories pushed by pro-Russian sources and low willingness to get vaccinated. Although there were efforts on social media platforms to curb the infodemic, work by an activist group Avaaz suggests that more than half of Facebook content in major non-English European languages was not acted on.

A study of how Russia, China, and Iran shaped narratives about vaccines was conducted by Bret Schafer and colleagues, of the Alliance for Securing Democracy. They analysed almost 30,000 vaccine-related tweets from Russian, Chinese and Iranian officials and state media outlets. They found few examples of verifiably false information, but reports of safety concerns were sensationalised.

WHO cares?

Unfortunately, America also used misinformation in its attacks on the World Health Organisation (WHO) to achieve political goals. The attacks were part of an attempt to deflect blame for its poor response to covid in the run-up to a challenging election for the president. After months of harsh words directed at the WHO by the American president, in May 2020 the health secretary Alex Azar said at the World Health Assembly:

We must be frank about one of the primary reasons this outbreak spun out of control: There was a failure by this organization to obtain the information that the world needed, and that failure cost many lives.

It is ridiculous to suggest that an UN agency should have been more capable than the American government in extracting more information about the true nature of the outbreak in the early days of the pandemic. But there were also charges that its response was sluggish, and its praise of China (which was supposed to be because the organisation was controlled by that country). Yet WHO’s initial stance towards China was perfectly aligned with that of America. Scott Gottlieb, a former FDA boss, recounts in his book that the American president deliberately heaped praise on China at the start of the pandemic. He says Mr Trump felt he got “more with sugar than with salt when it came to Chinese leaders”.

In one meeting, Mr Trump said that if he was tougher on China it would be “even less forthcoming with information”. Dr Tedros, head of the WHO, seems to have made the same calculation. And as for the sluggish response, it is clear the WHO was short of actionable information. America, though, knew more, earlier on, than it was saying, and might have acted differently. Mr Trump, for example, admitted that he deliberately downplayed the virus. As 2020 moved on, Mr Trump became more openly critical towards China. America wanted the WHO, and Dr Tedros to follow suit.

In May 2020 I spoke to Lawrence Gostin, who runs the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law in Washington D.C. He explained that the health assembly that year, which was focused almost entirely on the pandemic, was taking place in the context of a huge geopolitical competition between the two world superpowers. The WHO was caught in the middle. America hoped to throw its weight around, and try to get accountability from China—particularly in relation to the origin of the virus. But ironically, America’s moves against the WHO caused it to lose influence when it was most needed.

The politics were also a huge distraction for the WHO. “You can’t even calculate it,” said Mr Gostin “WHO is trying to paper over the cracks, trying to act normally, but it is also acting defensively and continuing to remind the world about what it did in the past, rather than focusing on what it should do in the future”. A source within an international health NGO told me that for the WHO this sort of conflict, “stresses a system that is entirely overstressed to begin with”.

In this book, Dr Gottlieb recalls how he tried to dissuade the president from pulling out from the WHO. Dr Gottlieb said it would weaken the global health organisation at a key moment, and suggested the US should signal its displeasure with China by moving to include Taiwan in the upcoming health assembly. In the end, America did both. Along the way, these political gambits caused reputational damage to the WHO, and cost more wasted time on politics rather than health. The announcement to withdraw was made on an impulse by Trump in order to jazz up a speech that was “a bit meh”, according to the book by Shari Markson, “What Really Happened in Wuhan?”.

The American ambassador to Geneva, Andrew Bremberg, was blindsided by Trump’s impulsive announcement. He drew up a long list of American demands that he presented to Dr Tedros to win some concessions to take back to Washington in the hope of convincing the president to change his mind. In Markson’s account of what happened, Dr Tedros was “proud by nature” and hurt by the president’s criticism of his leadership and didn’t want to be seen to be caving to America’s demands.

In August of 2020, I met Dr Tedros in Geneva. He told a different story. He had very much wanted America to remain, and said “we tried our best to reverse that”. As we sat in his well-ventilated office overlooking the Geneva hills, he said America’s involvement in the WHO was not about the money it brought but about its leadership and commitment to global health. He recalled how important American support had been in Ethiopia.

I was a minister of health in Ethiopia, when PEPFAR started to be operationalized. And this was, you know, during President Bush's time. And I remember when I became minister there was no one that was on HIV/AIDS treatment. And people were dying in Ethiopia and in other countries. And you see people in despair. You know individuals, families in despair. And everybody was feeling really helpless. And then what the United States brought with PEPFAR was hope.

In the end, he says America set “completely unacceptable” conditions for remaining inside the WHO. He added, “whatever request is unfair, which is not right, I will not accept. At the end of the day, I need to do what I believe. I need to stick to the truth. I get my peace if I am internally OK, when I do what I believe.” Dr Tedros does not strike me as a man that is proud. Although he is stubborn.

I don’t go for something I don’t believe. And they say ‘OK, China is paying him' and so on. Nobody can buy me. Nobody. They can’t and they don’t. I say no to China, I say no to the US, I say no to any country on Earth. And that is the challenge, by the way, and this process makes the DG independent. I’m not anybody’s appointee.

Dr Tedros also pointed out that while America had highlighted China’s withholding of information about the early days of the pandemic, the country had not provided information to support its statement that the outbreak started in November. He said, “if something starts in China, and other countries knew, they have … the obligation to inform us.” (A previous post talks about November cases.)

In some countries they politicised… and leaders were trying to push back rather than focus on the real world. Dr Tedros, August 2020.

“Following the science”

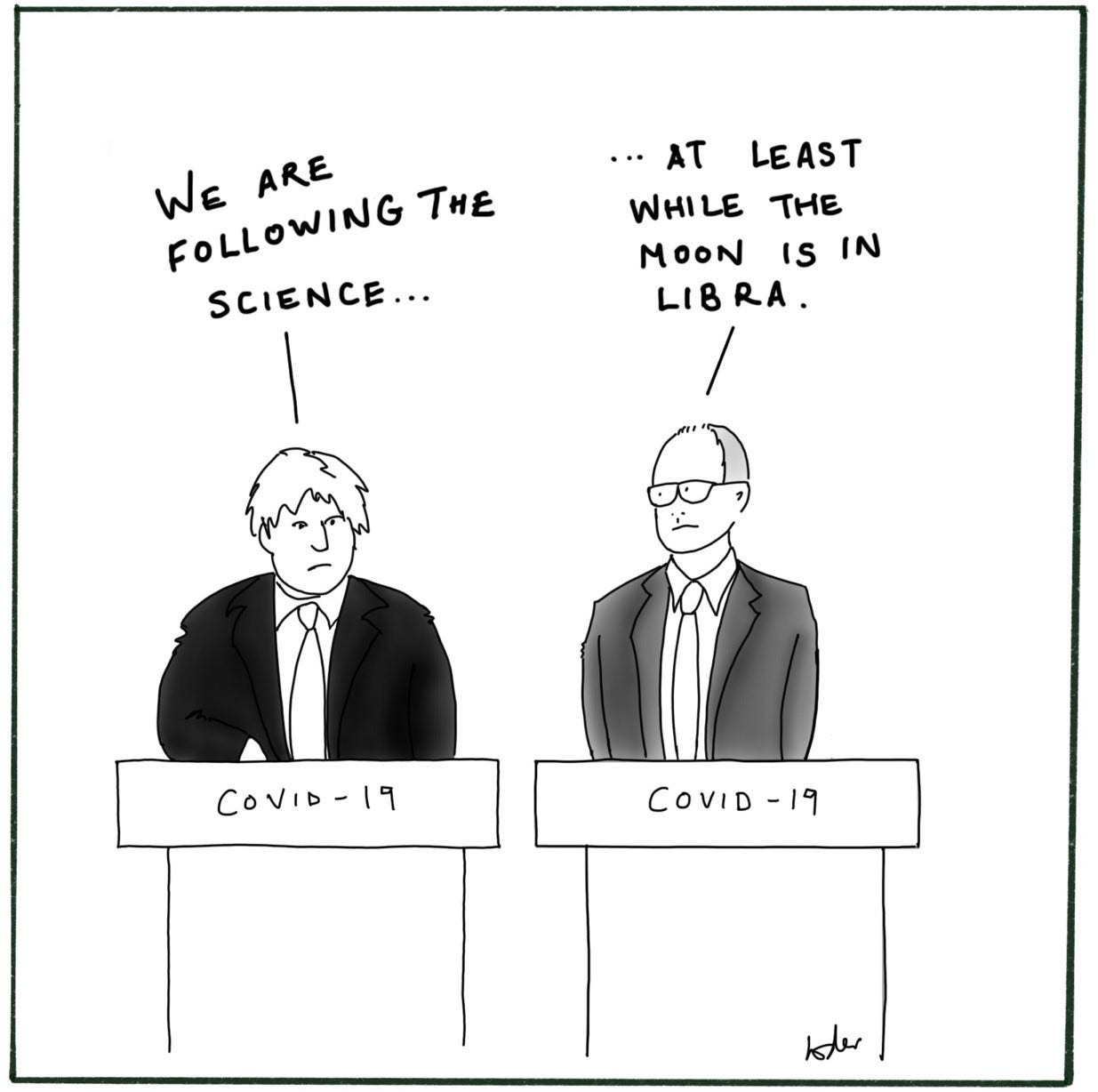

Over in Britain, ministers proclaimed they were “following the science”. They were not. In the book “Spike”, Jeremy Farrar of the Wellcome Trust, along with journalist Anjana Ahuja, recount how the government was told as early as February of the benefits of non-pharmaceutical, behavioural, and social interventions, and how these would slow the spread of the new virus.

On March 3rd the politicians came up with a strategy that was introduced by UK prime minister Boris Johnson. He said, “for the vast majority of the people of this country, we should be going about our business as usual.” The disastrous nature of the policy was spelled out on March 12th by a politician from Johnson’s own party. The delay in announcing a lockdown, which came on March 23rd, cost many lives.

There was more that was problematic about the “following” of science in Britain. Saying this sort of thing, while standing next to scientists when announcing politically difficult decisions looks like an attempt to shift the blame. In June 2020, I spoke to James Wilsdon, a professor of research policy at Sheffield University. He expressed unease at how far out in front of the public response scientists were being put. He recalled that early on in the pandemic, when Matt Hancock, then Britain’s health minister, was asked how many people working in England’s state-run National Health Service had died, the minister turned the question over to the deputy chief medical officer—a scientific civil servant.

How should science and policy-making work together? Around the same time, I talked with Holden Thorp, editor in chief of Science, and he said that in an ideal world, policy decisions would be made on the basis of strongly substantiated scientific research. This, he says, goes all the way from how to manage lockdowns, via basing social-distancing rules on epidemiology, to how long it might reasonably take for pharmaceutical companies to come up with drugs and vaccines. There will always be uncertainties and this is where the art of policymaking comes in. Policy, says the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, a British think-tank, must be based on a mixture of goals, costs, and facts. Politicians, ultimately, must make the choices. Sometimes they will be easy. (The decision to vaccinate.) At other times these decisions will be hard. (The decision to lockdown.)

Did we have a post-truth pandemic?

It was against the backdrop of the end of the second world war that the world decided it needed a new department of public health. Andrija Stampar, a round-faced, bespectacled, Yugoslavian doctor, opened the first-ever World Health Assembly in 1948. In the midsummer of that year, this meeting of many nations in Geneva birthed the WHO. The leading lights of global health assembled to listen to Dr Stampar speak of the spirit of optimism that drove the effort to create the WHO. He explained how, along the way, differences of opinion had been settled, amicably, by friendly agreement. Almost three-quarters of a century on and much has changed.

In 2016, the Oxford Dictionary chose “post-truth” as its word of the year, defining it as “relating to circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”. That has certainly been the case many times in the last few years.

The scale and nature of the misinformation have felt extraordinary at times. Mr Dov Bachmann et al. concur, “What is different during the covid pandemic is the pace of disinformation propagation”. The authors highlight an elevated level of politicised content. “This is the first global crisis where major powers are messaging to promote and advance their parochial interests, whether because of nationalism arising from the pandemic threat or because of global competition”. A second reason to think that is our first post-truth pandemic is thanks to levels of “artificial amplification”. Bots, trolls, and syndicated news outlets (think of China’s Global Times) propagate misinformation around the world.

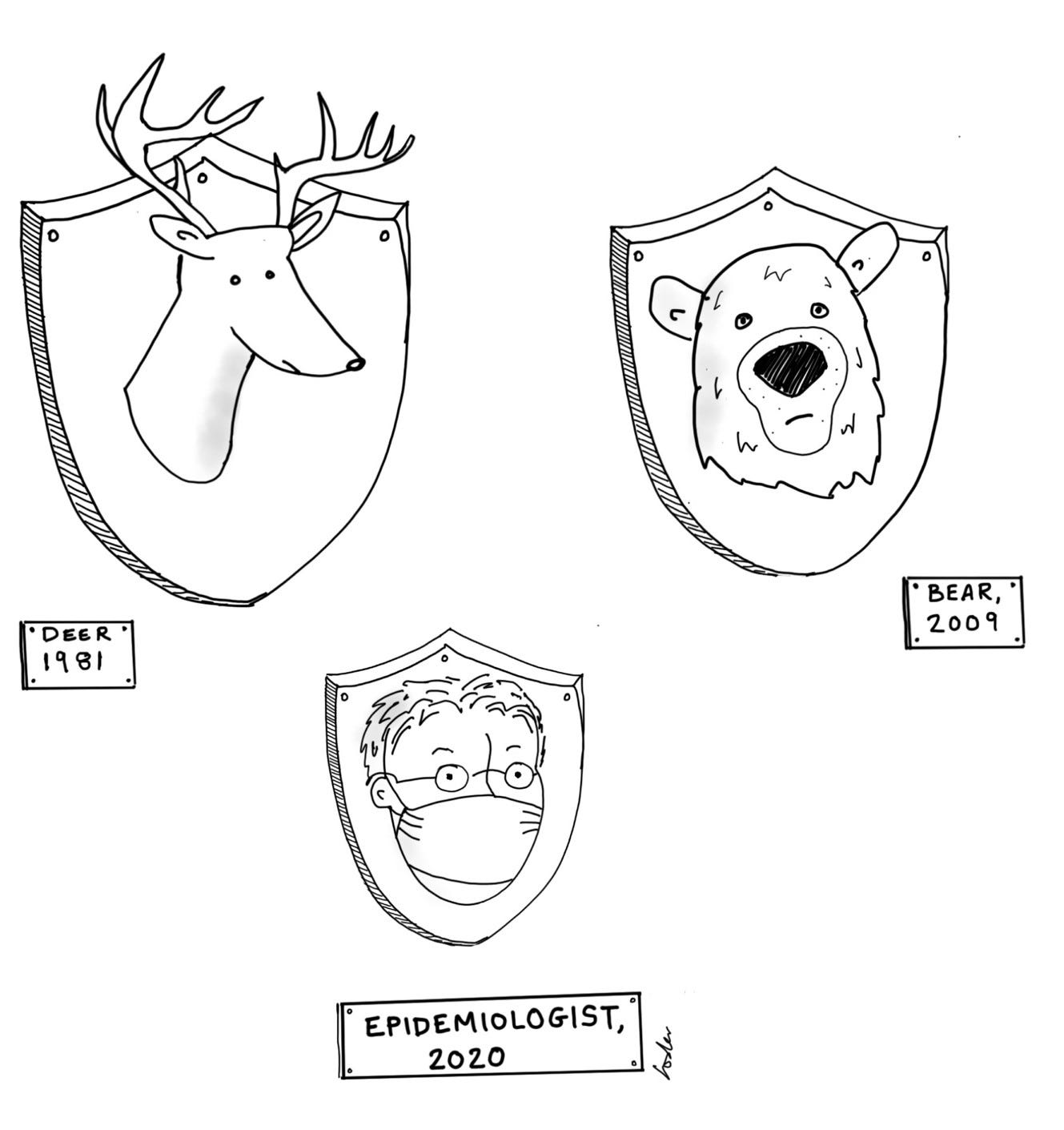

The misinformation, disinformation, politicisation, and conspiracy theories have taken scientific time away from work on the pandemic. It means, says Dr Thorp, doing everything we can to "get people to understand what's real". It is also undermining confidence in scientists and public health advice. Post-truth attitudes towards the outbreak have done real harm. It has driven people to drink dangerous substances, seek out treatments that do not work, and frightened people away from taking vaccines (which do work). It has driven hostility towards masks—a useful health intervention—and even driven anger towards hardworking scientists, doctors, and public health officials.

It is not the first time that politics or misinformation has fuelled poor outcomes during an outbreak of disease (think of the idea that AIDS could be transmitted through casual contact, or that it was a gay “plague”, or that abstinence rather than condoms were the solution). But the pervasive nature of misinformation and disinformation and politicisation of health for political goals seems remarkable.

At the height of the cold war, America and the Soviet Union managed to work together to eradicate smallpox. Dr Gostin feels that in matters of public health that politics and ideology need to be set aside. That cleaves strongly to the Stamparian vision and spirit which gave birth to the WHO. Today that vision feels in rather short supply with America and China at odds over covid. And if this account is less critical of Russia and China than it could be, it is simply because my expectations were lower.

As we head into the third pandemic year—now packing vaccines, antibody therapies, steroid treatments, and two new antiviral drugs—the tools we have to fight covid-19 come thanks to research, clinical trials, and, above all, facts. Science is ultimately self-correcting, and tends to converge on the truth. But, as John Barry, author of “The Great Influenza” wrote last year, “when you mix science and politics, you get politics”. In an era when we had the tools and technology to do far better, many leaders have failed to place a priority on the protection of human life.

Updates

Short updates to this story will be posted here. Please do comment in the chat if you want to challenge any of the analysis. And do let me know if there are any errors of fact in this item. Changes will be noted here.

But see https://euvsdisinfo.eu/uploads/2021/04/EEAS-Special-Report-Covid-19-vaccine-related-disinformation-6.pdf/

Amazing work, excellent information, sources and analysis,

This is good work – the list of absurd comments particularly eye-catching. To me almost all the types of actors of importance – including the scientists, you don't mention daszak – seem covered in disgrace.